Consanguinity, Genetics and Art, Part 2

Genetics and Art: a series with Dr. Bassem Bejjani

Dr. Bejjani is a medical geneticist who has practiced in academic and private settings for more than 30 years and published around 100 peer-reviewed papers in the genetics and genomics field. He is the Chief Medical Officer of Metis Genetics. He is past Chair of the Washington State Arts Commission and Vice President of Caravan, an interfaith art organization. He currently serves on the boards of WESTAF (Western States Art Federation) and The Henry Art Gallery at the University of Washington. Dr. Bejjani will discuss the interplay between the worlds of genetics and art in this blog series.

Consanguinity, Genetics and Art, Part 2

In Part 1 of this blog series, we discussed that individuals and societies have engaged in consanguineous marriages throughout history in order to conserve power and wealth within families. This practice has been documented in several cultures and civilizations, from ancient Egypt to the royal families of Europe, to the contemporary Middle East.

Consanguinity is currently practiced by up to 10% of the world’s population, with rates ranging from 80.6% in certain areas in the Middle East, to less than 1% in western societies. It predates Islam and has been practiced since at least Old Testament times.¹

Consanguinity’s Effect on Health

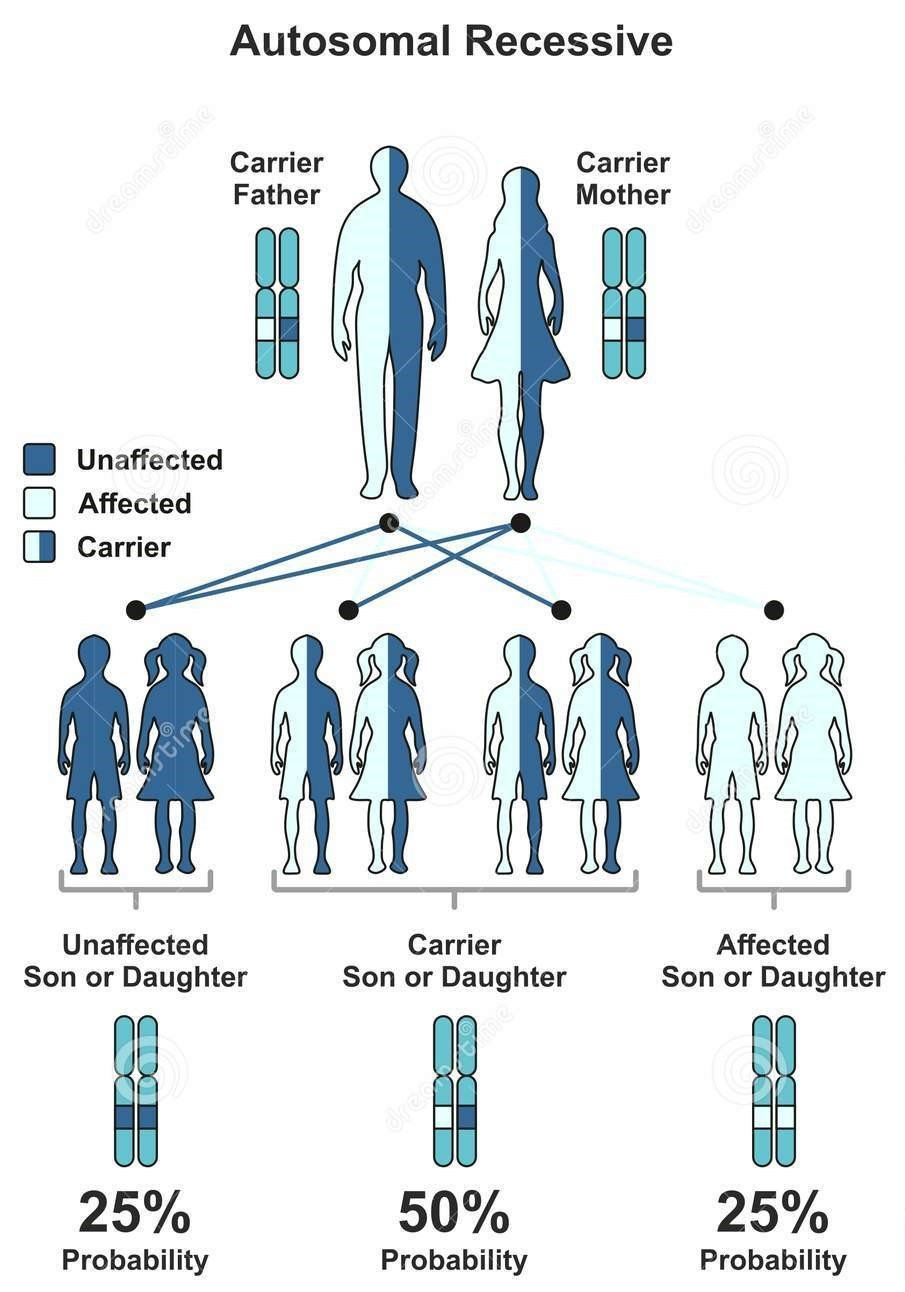

Consanguinity has a major effect on health and can give rise to a host of medical issues and genetic diseases. Congenital malformations have been established to occur more frequently in consanguineous couples above the background rate (4.5% vs. 1%), due to the “founder effect”, or having common ancestors. Consanguinity is most commonly associated with inborn errors of metabolism, most of which are inherited in an autosomal recessive manner.¹ Inborn errors of metabolism are more common in families with higher rates of consanguinity leading to higher morbidity and mortality. In fact, first cousins have a 1.5% to 3% increased risk of having a child with inherited birth defects over the general population risk of unrelated individuals. First cousins once removed, have an increased risk of 0.75% to 1.5%, and second cousins have no higher risk than a genetically unrelated couple. Double first cousins are infrequent but have approximately twice the risk of first cousin relationships of having a child with inherited birth defects.²

In an autosomal recessive disease, both copies of a gene have a change, or variant that affects the gene’s ability to behave as it normally should. Typically, a person with an autosomal recessive genetic disease has inherited a variant from each of his or her parents and does not possess a working copy of the gene. The absence of a functioning gene and resulting lack of gene product cause disease. Individuals who are blood relatives are more likely to be carriers for the same recessive disease condition(s), hence the risk of autosomal recessive genetic disorders is higher in children born from consanguineous unions.

Studies have also revealed a higher incidence of other diseases in consanguineous populations, with a significant increase in the prevalence of common adult diseases such as diabetes mellitus, cancer, blood disorders, intellectual disabilities, heart diseases, asthma, gastro-intestinal disorders, hypertension, hearing deficits and common eye diseases.³

Recognizing Consanguinity in Healthcare

It is important for healthcare providers to recognize consanguineous families, and to be transparent about the health risks in such situations. It is estimated that one billion individuals live in communities with a preference for consanguineous marriage. Consanguineous marriage is traditional and respected in most communities of North Africa, the Middle East and West Asia, where intra-familial unions collectively account for 20–50% of all marriages.⁴ Providers should be aware of the distinct possibility of consanguinity in patients residing in these areas, as well as in immigrants from these communities currently residing in North America and elsewhere.

In clinical genetics, a consanguineous marriage is defined as a union between two individuals who are related as second cousins or closer, with the inbreeding coefficient (F) equal to or higher than 0.0156. F represents a measure of the proportion of loci (genetic locations) at which the offspring of a consanguineous union is expected to inherit identical gene copies from both parents. This includes unions termed first cousins, first cousins once removed, and second cousins. In some communities, the highest inbreeding coefficients are reached with unions between double first cousins, and uncle–niece marriages, where F reaches 0.125.⁴

In order to help detect families in which consanguinity may be present, providers should continue to be aware of the ethnic background of their patients. In addition, when counseling individuals or couples about genetic risks, providers should ask the question: “Is there any possibility that you (or other couples in your family) may be related outside of marriage?” Using the answers to this question to help draw a family tree, or pedigree, can help to narrow down the particular risks that a patient or family may be facing as a result of consanguinity. The false belief that inherited disorders can only arise through cousin marriages on the paternal side of the family is quite common, therefore in the minds of some people, consanguinity may refer only to paternal blood relationships. Thus, during counseling, if a couple indicates that they are not related, it is important to specifically inquire about any shared biological relationships on their mothers' sides of the families as well.⁴

Counseling Families about Consanguinity

In preconception genetic counseling of a couple, if there is no known genetic disorder in the family after a four-generation pedigree or family tree is obtained, first cousin marriages are generally given a risk for birth defects in the offspring that is double the population risk (a 1.5% to 3% additional risk over the general population risk for unrelated individuals). As stated above, first cousins once removed have an increased risk of approximately 0.75% to 1.5%, and second cousins have no higher risk than a genetically unrelated couple. Double first cousins have approximately twice the risk of first cousin relationships of having a child with a genetic condition.²

If the family history indicates the presence of a specific genetic disorder, then the primary health care provider should refer the couple to a specialized genetic counseling clinic. This can help in estimating the precise risks to the offspring and in diagnosing the couple’s carrier status for autosomal recessive disorders known to be present in the family, whenever such genetic tests are available and applicable.⁴

Although consanguinity may seem objectionable to individuals from Western societies, it is a common practice in a large proportion of the world’s population due to their cultural and societal norms. Out of respect for different cultures and these long-held traditions, healthcare providers can educate themselves on these practices and help to ensure access to preconception and premarital counseling services as a means to help improve overall health. Increasing public literacy on consanguinity is always helpful and should begin with the education and training of primary health care providers.

References:

1. O. Olubunmia, et al. A review of the reproductive consequences of consanguinity. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, Volume 232, January 2019, Pages 87-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.10.042.

2. M. A. Bhinder et al. Consanguinity: A blessing or menace at population level? Annals of Human Genetics. Volume 83, Issue 4, July 2019, 214-219. https://doi.org/10.1111/ahg.12308.

3. A. Bener, et al. Global distribution of consanguinity and their impact on complex diseases: Genetic disorders from an endogamous population. Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics. Vol. 18 No. 4 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmhg.2017.01.002.

4. H. Hamamy. Consanguineous marriages, Preconception consultation in primary health care settings. J Community Genet. 2012 Jul; 3(3): 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12687-011-0072-y.